Asia and Pacific

Regional Economic Outlook: Asia Pacific

May 2018

The world economy continues to perform well, with strong growth and trade, rising but still muted inflation, and accommodative financial conditions, notwithstanding some increased financial market volatility in early 2018. Driven partly by the procyclical tax stimulus in the United States, near-term economic prospects for both the world and Asia have improved from the alreadyfavorable outlook presented in the October 2017 Regional Economic Outlook Update: Asia and Pacific. Asia is expected to grow by around 5½ percent this year, accounting for nearly two-thirds of global growth, and the region remains the world’s most dynamic by a considerable margin. But despite the strong outlook, policymakers must remain vigilant. While risks around the forecast are broadly balanced for now, they are skewed firmly to the downside over the medium term. Key risks include further market corrections, a shift toward protectionist policies, and an increase in geopolitical tensions. With output gaps closing in much of the region, fiscal policies should focus on ensuring sustainability. Given still moderate wage and price pressures, monetary policies can remain accommodative in most Asian economies for now, but central banks should stand ready to adjust their stances as inflation picks up, and macroprudential policies should be used appropriately to contain credit growth. Many Asian economies face important medium-term challenges, including population aging and declining productivity growth, and will need structural reforms, complemented in some cases by fiscal support. Finally, the global economy is becoming increasingly digitalized, and some of the emerging technologies have the potential to be truly transformative, even as they pose new challenges. Asia is already a leader in many aspects of the digital revolution, but to remain at the cutting edge and reap the full benefits from technological advances, policy responses will be needed in many areas, including information and communication technology, trade, labor markets, and education.

Executive Summary

The economic outlook for Asia and the Pacific remains strong, and the region continues to be the most dynamic of the global economy. Near-term prospects have improved since the Regional Economic Outlook Update: Asia and Pacific in October 2017, and risks around the forecast are broadly balanced for now. Over the medium term, however, downside risks dominate, including from a tightening of global financial conditions, a shift toward protectionist policies, and an increase in geopolitical tensions. Given the many uncertainties, macroeconomic policies should be conservative and aimed at building buffers and increasing resilience. Policymakers should also push ahead with structural reforms to address medium- and long-term challenges, such as population aging and declining productivity growth, and to ensure that Asia is able to reap the full benefits of increasing digitalization in the global economy.

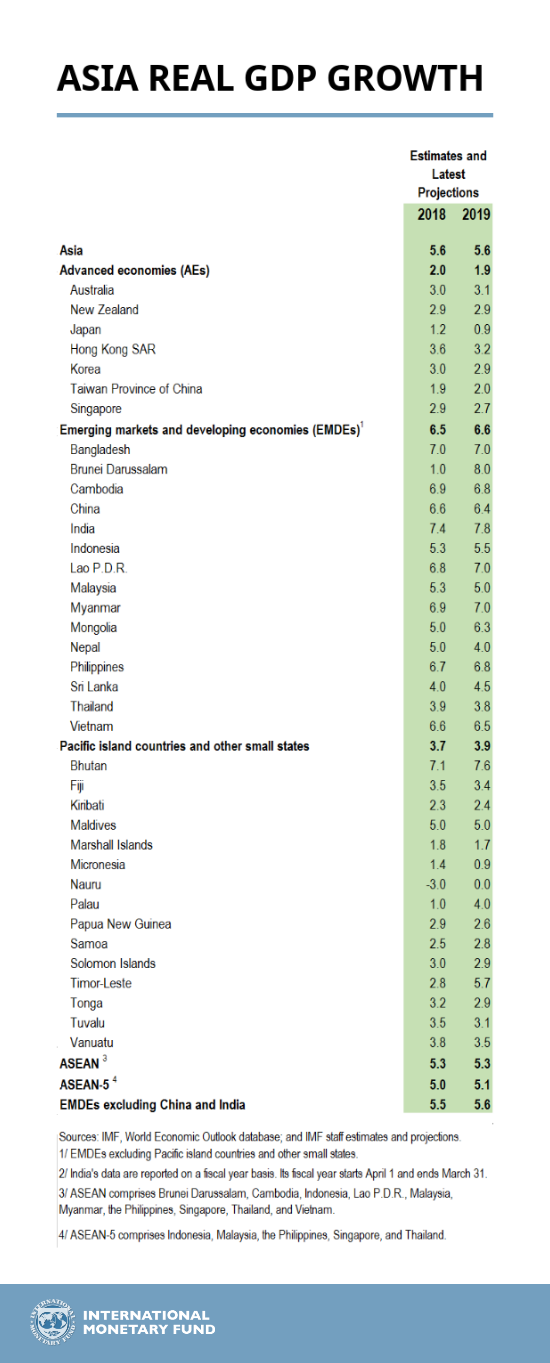

Growth in Asia is forecast at 5.6 percent in 2018 and 2019, while inflation is projected to be subdued. Strong and broad-based global growth and trade, reinforced by the US fiscal stimulus, are expected to support Asia’s exports and investment, while accommodative financial conditions should support domestic demand. China’s growth is projected to ease to 6.6 percent, partly reflecting the authorities’ financial, housing, and fiscal tightening measures. Growth in Japan has been above potential for eight consecutive quarters and is expected to remain strong this year at 1.2 percent. And in India, growth is expected to rebound to 7.4 percent, following temporary disruptions related to the currency exchange initiative and the rollout of the Goods and Services Tax.

Risks around the outlook are balanced for now but tilted to the downside over the medium term. On the upside, the global recovery could again prove stronger than expected, and over time the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and successful implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative—assuming debt sustainability and project quality are maintained—could both support trade, investment, and growth. On the downside, Asia remains vulnerable to a sudden and sharp tightening of global financial conditions, while too long a period of easy conditions risks a further buildup of leverage and financial vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities could be exacerbated by excessive risk taking and a migration of financial risks toward nonbanks. The gains from globalization have not been shared equally, and, as highlighted by recent tariff actions and announcements, a shift toward inward-looking policies is another risk, with the potential to disrupt international trade and financial markets. Geopolitical tensions remain another important source of risk. Finally, cybersecurity breaches and cyberattacks are on the rise globally, and climate change and natural disasters could continue to have a significant impact on the region.

Long-term growth prospects for Asia-Pacific are impacted by demographics, slowing productivity growth, and the rise of the digital economy. One important challenge is population aging, as many economies in the region face the risk of “growing old before they grow rich,” and the adverse effect of aging on growth and fiscal positions could be substantial. A second challenge is slowing productivity growth. Finally, the global economy is becoming increasingly digitalized, and while some recent advances could be truly transformative, they also bring challenges, including those related to the future of work. Asia is embracing the digital revolution, albeit with significant heterogeneity across the region.

Chapter 2 analyzes the factors behind low inflation despite strong growth, and how long this is expected to last. The findings highlight that temporary global factors, including imported inflation, have been key drivers of low inflation. And indeed, in line with an upturn in oil prices over recent months, headline inflation in the region has picked up, while core inflation has remained subdued and below target in many economies. Second, while inflation expectations are generally well anchored to targets, the influence of expectations in driving inflation has declined, as the inflation process has instead become more backward looking. Third, there is some evidence that the sensitivity of inflation to economic slack has diminished—in short, the Phillips curve has flattened.

Inflation in the Asia-Pacific region may increase once global factors, including US inflation and commodity prices, become less favorable, and policymakers should stand ready to act. In addition, higher inflation may persist on account of the increasingly backward-looking inflation process. And with a flatter Phillips curve, the output cost of disinflating could be higher. Accordingly, policymakers should be vigilant in responding to early signs of inflationary pressure, though the response to commodity price shocks should be to accommodate first- but not second-round effects. Improved monetary policy frameworks and central bank communications could increase the role of expectations in driving inflation and thus make inflation less sticky. More flexible exchange rates could mitigate the role of imported inflation, and macroprudential policies can help address financial stability risks.

With output gaps closing in much of the region, continued fiscal support is less needed, and most economies in Asia should turn to strengthening buffers, increasing resilience, and ensuring sustainability. Some economies should also focus on improving revenue mobilization to create space for infrastructure and social spending and help support structural reforms. The strong economic outlook makes this an opportune moment to pursue such reforms. Tailored measures are needed to boost productivity and investment, narrow gender gaps in labor force participation, deal with the demographic transition, address climate change, and support those affected by shifts in technology and trade. And finally, to reap the full benefits of the digital revolution, Asia will need a comprehensive and integrated policy response covering information and communications technology, infrastructure, trade, labor markets, and education.

Chapter 1 - Good Times, Uncertain Times

The world economy continues to perform well, with strong growth and trade, rising but still muted inflation, and accommodative financial conditions, notwithstanding some increased financial market volatility in early 2018. Driven partly by the procyclical tax stimulus in the United States, near-term economic prospects for both the world and Asia have improved from the already-favorable outlook presented in the October 2017 Regional Economic Outlook Update: Asia and Pacific. Asia is expected to grow by around 5½ percent this year, accounting for nearly two-thirds of global growth, and the region remains the world’s most dynamic by a considerable margin. But despite the strong outlook, policymakers must remain vigilant. While risks around the forecast are broadly balanced for now, they are skewed firmly to the downside over the medium term. Key risks include further market corrections, a shift toward protectionist policies, and an increase in geopolitical tensions. With output gaps closing in much of the region, fiscal policies should focus on ensuring sustainability. Given still moderate wage and price pressures, monetary policies can remain accommodative in most Asian economies for now, but central banks should stand ready to adjust their stances as inflation picks up, and macroprudential policies should be used appropriately to contain credit growth. Many Asian economies face important medium-term challenges, including population aging and declining productivity growth, and will need structural reforms, complemented in some cases by fiscal support. Finally, the global economy is becoming increasingly digitalized, and some of the emerging technologies have the potential to be truly transformative, even as they pose new challenges. Asia is already a leader in many aspects of the digital revolution, but to remain at the cutting edge and reap the full benefits from technological advances, policy responses will be needed in many areas, including information and communication technology, trade, labor markets, and education.

Chapter 2 - Low Inflation in Asia: How Long Will It Last?

Global growth in 2017 was the highest since 2011 and is expected to strengthen further in 2018–19, supported by broad-based momentum across countries and fiscal expansion in the United States. Headline inflation has been picking up with the upturn in oil prices since September, but core inflation remains surprisingly subdued, especially in advanced economies. Asia has been in a sweet spot of strong growth and benign inflation. While GDP growth forecasts for 2017–18 have been repeatedly revised up over the last two years, inflation forecasts have been kept constant or revised down (Figure 2.1). Core inflation remains below inflation targets in many Asian economies (Figure 2.2).

Motivated by these developments, this chapter aims to shed light on the following questions: Why has inflation been low in Asia recently, and how long will it last? What has been the role of import prices and global factors? How well anchored are inflation expectations? To what extent has inflation become less sensitive to economic slack—that is, has the Phillips curve flattened? How do these drivers of inflation in Asia differ from those in other regions? Finally, what are the key implications for policymakers?

To address these questions, the chapter analyzes inflation dynamics relying on a variety of approaches, including estimation of augmented Phillips curves, principal component analysis to distinguish global factors from country-specific factors, and an analysis of trend inflation to shed light on how long low inflation is likely to persist.

The main findings are as follows:

- Recent low inflation has been driven mainly by temporary forces, including imported inflation. Phillips curve estimation indicates that weaker import prices, including low commodity prices, contributed to half of the undershooting of inflation targets in advanced Asia and most of the undershooting in emerging Asia in recent years. In addition, China seems to have played an important role in driving both global and regional inflation. More generally, an analysis looking at temporary and trend components suggests that temporary shocks have accounted for the bulk of the recent reduction in inflation.

- The inflation process has become more backward-looking. While inflation expectations are generally relatively well anchored, especially in advanced Asia and in economies with inflation-targeting frameworks, the importance of expectations in driving inflation has declined in recent years with past inflation playing a larger role.

- The sensitivity of inflation to the unemployment gap has declined. There seems to be a flattening of the Phillips curve compared to the 1990s in advanced Asia and a similar but more continuous flattening in emerging Asia. Outside of Asia, the slope of the Phillips curve seems to have been more stable.

Looking forward, these findings suggest that inflation may well rise in Asia as commodity prices and other temporary factors reverse themselves (the current WEO projects a near-term increase in commodity prices). Higher inflation in the rest of the world and weaker currencies in the region could pose upside risks to inflation. If such risks materialize, higher inflation may well persist, given the stickiness of the inflation process. And given the relative flatness of the Phillips curve, the output costs of disinflating may be high.

The main policy implications of the findings are:

- Central banks should be vigilant in responding to early signs of inflationary pressure, including from global factors. A sudden increase in inflation may then persist, and disinflating may be costly if sensitivity of inflation to the unemployment gap has declined.

- It will be important to strengthen monetary policy frameworks and improve central bank communications in order both to increase the role of expectations in driving inflation and to maintain expectations anchored to targets.

- To mitigate the role of imported inflation, exchange rates should be allowed to adjust more flexibly.

- In principle, the monetary policy response to commodity price shocks should be to accommodate first- round effects but not the second-round effects.